By Min Zan

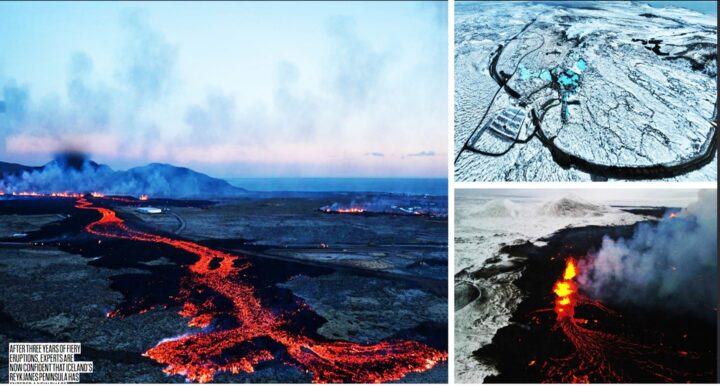

A big, angry monster woke up after sleeping for many, many years. In the past three years, it started making cracks in the ground in the southwest part of Iceland. It also spits out hot, melted rock called lava. People all over the world are amazed and scared by it. Experts say this monster, called the Icelandic fault line, was quiet for 800 years, but now it’s waking up again. This could go on for many years.

Iceland is a special place in the ocean. It has more than 30 angry mountains that can explode. It’s not uncommon for one of these mountains to blow up every three to five years. But sometimes, many of them wake up at once, and then they go quiet again. In the last 500 years, Iceland’s mountains have sent out a lot of lava, about one-third of all the lava on Earth.

Iceland is so angry because of where it sits on Earth. It’s on a crack between two big pieces of Earth’s outer shell. These pieces are slowly moving away from each other, making the crack bigger. Iceland also sits right above a place where the hot melted rock comes up from deep inside the Earth.

The hot rock comes from way down, over 1,200 miles under the ground. There aren’t many places on Earth where both the crack and the hot rock are so close together. This makes Iceland special, according to Magnús Tumi Guðmundsson, who teaches about Earth at the University of Iceland.

Fire And Ice

Iceland is a place of opposites. Even though it’s very hot with all the volcanoes, it’s also icy because it’s near the North Pole. About 11 per cent of Iceland is covered in ice. Some of the mountains have ice on top of them, and when the hot lava meets the ice, it explodes. This happened in 2010 with a mountain called Eyjafjallajökull. The explosion sent bits of rock into the air, and many flights around the world got cancelled because it wasn’t safe to fly.

Another dangerous mountain in Iceland is Katla. It’s one of the biggest, and it’s under a thick layer of ice. If Katla were to blow up, it would melt a lot of ice and cause big floods. Katla last blew up in 1918, and people are watching it closely in case it wakes up again.

The Reykjanes Peninsula is right on top of a big crack in the ground called the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. There are four mountains there that sometimes wake up and throw out hot rocks. This happens every 800 to 1,000 years. Magnús Tumi Guðmundsson says this happens in episodes, which means there are times when the mountains are very active. During these times, there are eruptions every 20 to 30 years.

The last time the mountains on the Reykjanes Peninsula erupted was a long time ago, in the 12th century. They were very active between the years 1211 and 1240 AD. This was called the Reykjanes Fires. The Reykjanes and Eldvörp-Svartsengi mountains were both very angry at that time. They threw out a lot of hot rock and made big fields of lava. After that, everything became quiet for 800 years.

But now, things are not quiet anymore. In early 2020, scientists noticed earthquakes and the land moving near a mountain called Þorbjörn. This is about 40 kilometres south of Reykjavík, the capital city of Iceland. Scientists thought this might mean the mountains were waking up again.

Their suspicions grew stronger when the Fagradalsfjall mountain erupted dramatically in March 2021. A big crack opened up in the mountain, and hot rock shot out of it for almost six months. Then, after a little break, it erupted again in August 2022. In the summer of 2023, another crack opened on a nearby mountain called Litli-Hrútur, and lava flowed out.

In late October, after the Litli-Hrútur eruption, things got active again. Magma started moving up near Þorbjörn mountain. This made the ground rise by about six centimetres in just 12 days. Then, in early November, there were thousands of small earthquakes near the town of Grindavík, which made people worry another eruption was coming. The town was evacuated, and people waited anxiously to see what would happen. Finally, on December 18, a big crack opened north of Grindavík, and lava started shooting out.

Even though these recent eruptions were not very big compared to other ones in Iceland, they are still worrying because they are so close to where people live and important buildings, like the Svartsengi power station, which gives electricity and hot water to the peninsula. Magnús Tumi Guðmundsson says it’s serious because of this, not because the eruptions were very huge.

The Keflavík airport in Iceland is on the Reykjanes Peninsula, but it’s not in danger from the lava, so it’s stayed open during the recent eruptions. Another famous place, the Blue Lagoon, is also on the peninsula near the eruptions. But it’s been closed for safety reasons. Reykjavík, the capital city, is just a few kilometres away from the peninsula. Lots of people in Iceland live there. Like the airport, Reykjavík is not in the danger zone, but it’s close enough to the eruptions that tourists and people who love volcanoes can easily go see them.

Friendly for Tourists In Iceland, where people have lived near big volcanoes for thousands of years, some eruptions are called “tourist eruptions.” These are eruptions that are not very big, and people can predict when they will happen. In other places, people might run away from a volcano, but in Iceland, these eruptions can bring in lots of tourists. The Fagradalsfjall eruptions in 2021 and 2022 were like this. They were easy to get to and pretty safe to watch. They went on for weeks or months, so people had time to plan a trip. Many tourists came to see the flowing lava.

But this winter, the eruptions were different. They were more explosive and shorter, and experts told tourists to stay away. The eruption in December was especially different, according to Guðmundsson.

Preparing for Trouble Last November, when people started worrying about another eruption, the government started doing things to protect important buildings. They built a big wall to keep the lava away from a power plant. They finished the wall in December and then started building another wall near Grindavík, a town close to the eruptions. They hoped this wall would stop the lava from going into homes and businesses. But it wasn’t finished when the next eruption happened.

On January 14, there were over 200 small earthquakes. Then, two cracks opened up north of Grindavík. The cracks were further south than people expected, and it surprised everyone. The first crack went towards the new wall, but the second crack went past the wall and towards the town. One person said it was the worst thing that could happen to Grindavík.

The lava destroyed three houses, and the moving ground broke water pipes and power lines. People in Grindavík were very surprised and scared. But the wall did help. It stopped most of the lava from destroying the town.

Scientists have fancy tools to help them watch for signs of eruptions in places like the Reykjanes Peninsula. But it’s super hard to know exactly when or where a volcano will erupt.

The recent eruptions in Reykjanes have been caused by long cracks in the ground called fissures. These are harder to predict than eruptions from tall, pointy mountains that we often see in movies. Scientists can guess where an eruption might happen by looking at how the ground moves and by watching for earthquakes. This is how they knew to tell people in Grindavík to leave before an eruption happened in November. This warning helped save lives. But even with all their fancy tools, scientists can’t say for sure when or where an eruption will happen. Once they see magma moving under the ground, they can’t say if it’ll come out in a few days, weeks, months, or not at all.

Scientists in Iceland have different tools to help them guess when a volcano might erupt. They use things called seismometers to listen for lots of small earthquakes. These earthquakes can mean that magma is moving underground. Sometimes, earthquakes happen before an eruption, giving people time to get away.

They also use special GPS machines to see if the ground is rising. This can happen when magma is moving underneath it. Magnús Tumi Guðmundsson says these machines can show where magma is gathering underground. Pictures from satellites can show where the ground is getting higher because of magma moving under it.

Even with all this cool technology, it’s still hard to say what will happen in Grindavík and the Reykjanes Peninsula. Some people had to leave their homes because of the recent eruptions. Even though some went back, they had to leave again when the volcano woke up again in January. They don’t know when they can go back for good.

The Reykjanes Peninsula has been quiet for 800 years, but now it’s waking up again. There have been more earthquakes there in the past few years than ever before. But even though we can guess that there might be more eruptions in the next few months or years, nobody knows for sure.

Experts think that eventually, all the magma near the surface will come out, and things will calm down again. But based on what’s happened before, it could take many decades or even longer for the Reykjanes fault line to go back to sleep. We can’t be sure what will happen next.

Reference: BBC Science Focus Feb 2024